Homework in the AP Physics C Course

Including:

Introduction

A few general notes regarding homework in the course:

- You will typically be assigned approximately 3-5 homework problems per night, the problems being of varying difficulty.

- You need to complete the homework every night—physics, like math, is highly sequential in nature, and you will quickly find yourself falling behind in the course if you don't manage to stay on top of the material. Usually, your completed homework assignment from the previous night will be collected at the beginning of class.

- The homework problems have been carefully selected by the instructor to help you practice material that we've learned, and to give you experience attempting problems that you may not initially understand how to solve.

- You are encouraged to use the many resources available to you to help you solve these problems, including the book, other students, the instructor...

- Although the answers to these homework problems will usually be available to you, what is important is demonstrating that you know how to solve the problem (having furrowed the neurological pathways in your brain that is associated with problem solving at this level is what is going to get you by on a test). You will demonstrate your abilities to do this by turning in a well-written solution or explanation for the problem.

- You are encouraged to work with others as you study, but in the end, it's important for you to have your own understanding of the material. Likewise, the work you do on the homework should be your own and not copied from anyone else. See the Academic Integrity section for a more complete explanation.

- Often, you'll find that getting the correct answer to a problem will require several attempts, with work needing to be redone. It is expected that the new work written in a different color of ink for easy identification (see example below).

Much of the work that we do in this class consists of solving mathematical problems, with the occasional need to execute derivations. Although it's important for you to get the correct answer to the problems, it's even more important for you to learn how to get the answer. When your teacher asks you to graph the equation y=3x2-2x+4, it's not because anyone desperately needs to see the graph--it's because we want to know if you understand how to graph that equation. When you look at it from this perspective, the answers to your homework problems aren't as important as understanding the process by which you get the answers.

See below for more specific information on how to show your work.

A General Approach to Doing Homework

- Begin each problem on a blank sheet of paper. You will be using a single sheet of paper for each problem that you solve. (We'll discuss this in class.)

- After reading the problem, you need to do four things, more-or-less all at the same time:

--Make a very, very, very brief statement (a blurb) of what the problem is asking;

--Draw a sketch of the situation;

--Write down the variables and values that have been given in the problem statement; and

--Based on your experience and a little intuition, mentally figure out what approach you think will be appropriate to helping you solve the problem.

I will be modeling this process in class when we solve problems, and you'll be expected to be able to use this same process in your own problem-solving (note that in the video you will watch, the first part--the quick blurb--is not included--this was an oversight when the video was created).

- Select appropriate equations or formulae that you can use in your solution. If you have to derive an expression, follow the format provided on the YouTube video zPoly: 102 (formatting a physics derivation). If you don't have to derive anything but simply have to use already provided expressions, write down the equation(s) in variable form, then manipulate to get a final expression for the desired unknown value, clearly showing your steps.

- As you work, you'll write brief annotations ("blurbs") that will explain your reasoning, and the steps you've taken in your solution.

Annotating your work is an important part of your solution, and one that you might be tempted to overlook. In order to encourage you to develop good problem-solving habits, at the start of the year you'll be required to use a single page of paper for each single problem that you solve. That's right: one problem per page. Use as much of the page as possible, and be sure to include annotations of your work.

- As you work, you'll work vertically, not horizontally (that is, you will NOT put two relationships on one line but, rather, work DOWN THE PAGE).

- Substitute in known values for variables only after you get your final relationship, and box your final result.

- Check answer with known answer, if possible, and correct original work using a pencil/pen of a different color.

- Still don't get it? Identify the problem as one that you need additional help with, and contact another student or the instructor for help in how to solve it!

Examples of Homework (Good and Bad)

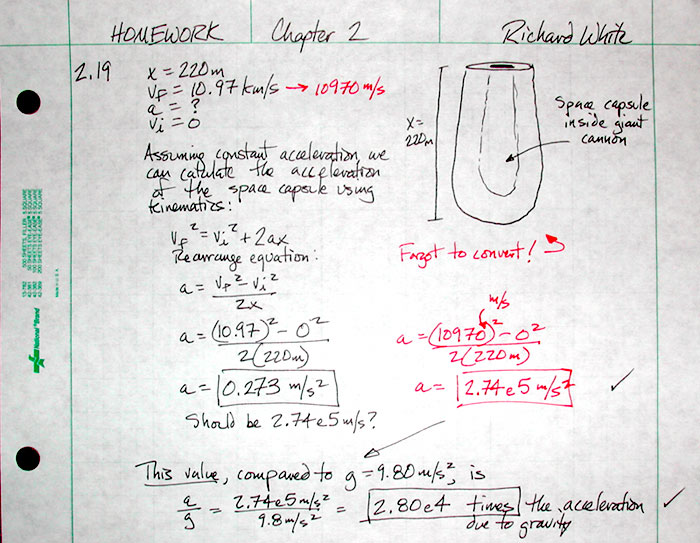

The original problem reads:

Jules Verne in 1865 suggested sending people to the Moon by firing a space capsule from a 200-m-long cannon with a launch speed of 10.97 km/s. What would have been the unrealistically large acceleration experienced by the space travelers during launch? Compare your answer with the free-fall acceleration 9.80 m/s2.

One essentially worthless solution is this first one. There is almost no information here for the instructor to examine, and no way of identifying whether the student understood the problem-solving process.

A correctly-written solution to this problem is given below. Note the use of "blurbs," brief written explanations of what is being done mathematically, and corrections that were added in red after the original work was done. Note also that the last line has two equations on it. This was done because Mr. White ran out of room. It is not something you should, in general, do . . . and I'd suggest you use scientific notation (i.e., x10 to a power) instead of the "e" notation favored by calculators.

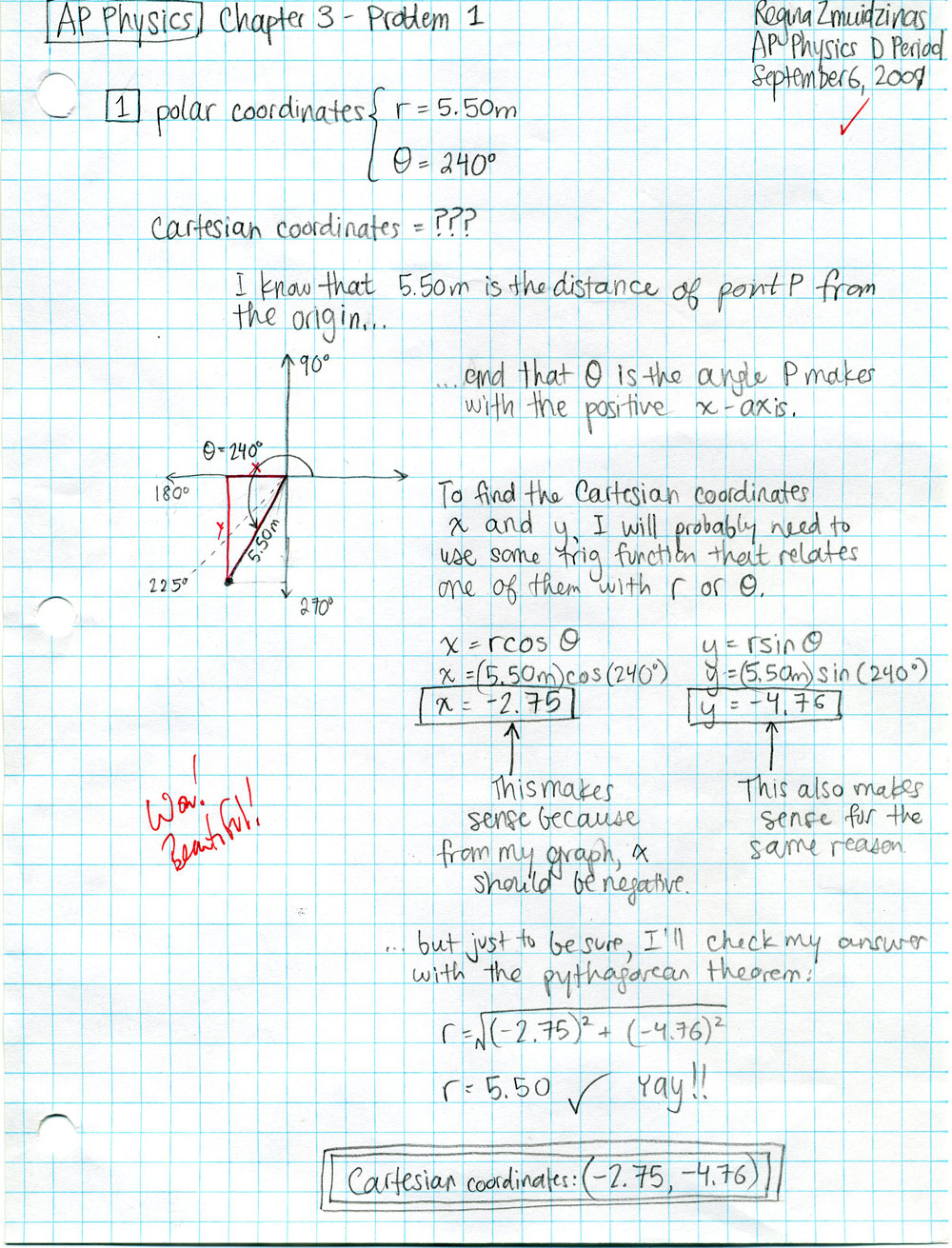

Here is another example of a student's work on a different problem. In this case, the student probably did more than was necessary with the blurbs (using short phrases and abbreviations is perfectly OK when blurbing). Remember, though some may take more time, you are, in theory, shooting for no more than 10 to 15 minutes per problem . . .